By Letícia Cesarino

In October 2018, Brazilians relived the shock many experienced in the US two years earlier, when Donald Trump was elected to the presidency. But Jair Bolsonaro’s landslide victory came as a surprise only to those who were not acquainted with the extensive digitally-mediated world where his campaign was almost entirely run. This is the terrain where I have been conducting digital ethnography. I started this research as a matter of personal urgency, in the aftermath of a ‘culture shock’ of sorts, when a close relative declared her intention to vote for the right-wing candidate. From my (progressive) perspective, their two profiles were incommensurable: her, a peace-loving, spiritualized, tolerant person; him, a homophobic, misogynous, racist, “repugnant other” (Harding 1991).

In October 2018, Brazilians relived the shock many experienced in the US two years earlier, when Donald Trump was elected to the presidency. But Jair Bolsonaro’s landslide victory came as a surprise only to those who were not acquainted with the extensive digitally-mediated world where his campaign was almost entirely run. This is the terrain where I have been conducting digital ethnography. I started this research as a matter of personal urgency, in the aftermath of a ‘culture shock’ of sorts, when a close relative declared her intention to vote for the right-wing candidate. From my (progressive) perspective, their two profiles were incommensurable: her, a peace-loving, spiritualized, tolerant person; him, a homophobic, misogynous, racist, “repugnant other” (Harding 1991).

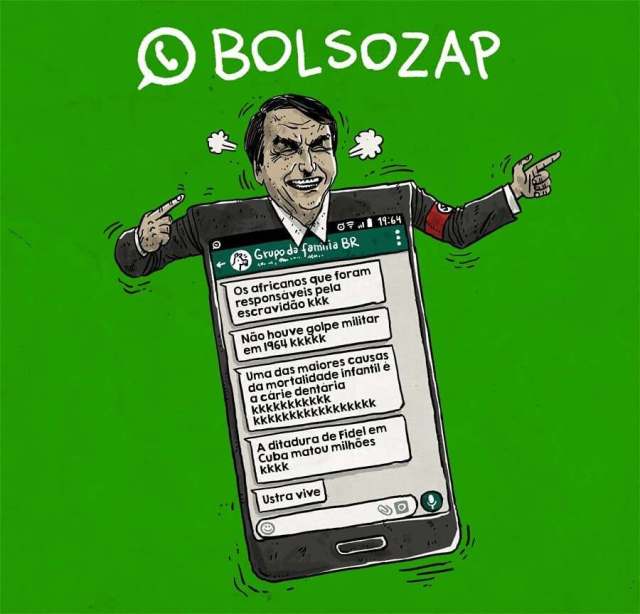

As my anthropological curiosity began pulling at the threads of her electoral preference – all of them digital, since we lived in different cities – I eventually realized that she was, quite literally, living in a different electoral world than mine. Rather than debating the candidates’ proposals and backgrounds, her communicative behavior on WhatsApp was largely limited to forwarding digital content of various kinds: short texts, long texts, memes, audios, videos, links to right-wing, ‘new media’ websites, and even PDF books. Through this medium, I eventually accessed a much wider network of pro-Bolsonaro digital supporters operating within a huge bubble, largely anchored in large WhatsApp groups, set apart from the mainstream public sphere by quite explicit norms: no “communist” content allowed and all “undercover” lefties will be banned. I quickly found out that by lefties and commies, they meant virtually anyone who was not part of the Bolsonarist camp (although there was always a potential threat of “internal” enemies). The prime target of these aggressions were mainstream politicians, artists, the media, and academic experts: in other words, any influencer that could provide them with an alternative perspective on their leader. Polarization accrued rapidly, in a process very much like the one Gregory Bateson (1972) called schismogenesis. Online behavior was effectively converted into offline election results – as early as in the first round, the poll became highly dichotomized between Bolsonaro and his “constitutive outside” (Laclau 1990), the Worker’s Party candidate Fernando Haddad.

Reports from the press at the time indicated that these digital bubbles were not formed as spontaneously as some claimed. Indications of paid bulk-messaging, scraping, bots and fake cell phones abounded, but were not investigated by the electoral courts (Magenta et al 2018). From a qualitative, ethnographic point of view, the less-than-spontaneous character of the digital content circulating in these bubbles was evident in the consistency of its underlying discursive patterns. Although during the campaign messages would arrive by the hundreds on a daily basis, virtually all such content could be classified in terms of five basic functions: to draw a friend-enemy frontier; to bolster the leader’s charisma and trace continuities between himself and his followers; to keep the public mobilized through alarmistic or conspiratory messages; to cannibalize and turn the opponents’ accusations around; and to displace mainstream sources of authoritative knowledge such as the press and academics.

Supporters hold a banner during the 38th presidential inauguration of Jair Bolsonaro, Brazil’s president, outside the Planalto Palace in Brasilia, Brazil, on Tuesday, Jan. 1, 2019. Former Army captain Jair Bolsonaro is being sworn in as Brazil’s president on Tuesday with the promise to tackle rampant crime, corruption and economic malaise in a wave of nationalism that’s sweeping Latin America’s largest country. Photographer: Patricia Monteiro/Bloomberg via Getty Images

These patterns were systemic in multiple senses: they structured discourse at the meta-communicative level of form rather than content; they operated as a complexity reduction mechanism, drawing a rigid inside-outside group frontier; they recurred at multiple scales; and they were efficacious in producing and stabilizing the “people” through a double, syntagmatic (we-them opposition) and paradigmatic (leader-people) axis. Readers of Ernesto Laclau (1990) and Chantal Mouffe (2005) will immediately recognize the pattern. Key to this strategy was also the mobilization of affect-loaded images and evocations, reminiscent of Mary Douglas’s classic thesis on group-formation and symbolic classifications along a pure-impure (dirty-clean; repugnant-virtuous; corrupt-righteous; good-evil) axis that demarcates a dangerous outside (Douglas 1966).

Although this mechanism no doubt reproduces much of what pre-digital populisms were about, in my view it has enough specificities to justify giving it a new name, for which I have chosen digital populism. Two aspects in particular have become more central as this classic tactic for building political hegemony becomes increasingly digitally-mediated: its fractal topology, and its recursivity. Mediation through smartphones and WhatsApp – both of which were not as extensively available in Brazil during the previous presidential election – afforded it unprecedented capillarity. From the individual user’s perspective, social media makes quite concrete the general (neoliberal) sense that intermediaries are no longer necessary: if you are lucky enough, your message on Twitter or WhatsApp may travel all the way to the president’s smartphone. Bolsonaro supporters often underscore how they did not care about politics before he came along – but that is only because the meaning of politics itself has changed to embrace a variety of emergent, digitally-mediated forms of individual and collective attitudes and identities, including a redefinition of what it means to be “right-wing” and “conservative”. A fortuitous event in late September intensified the capillarization effect afforded by digital media to a new level: the knife attack which removed the candidate from public debates, and led his supporters to assume the task of championing the campaign on his behalf. The candidate’s ailing physical body was thus fractally replaced by a vast, sprawling ‘digital body’ of voluntary marketers.

The Brazilian case therefore draws attention to an important point concerning the recursivity of digital populism, and its relation to neoliberal epistemology as understood by Philip Mirowski (in press). Given the ubiquity and consistency of the abovementioned discursive patterns, it is hard to believe that the construction of Bolsonaro’s digital campaign did not involve some kind of ‘science of populism’. But this recursivity between theory and practice becomes more powerful as it is fractalized across the digital landscape: anyone, anywhere with an internet connection is able to quickly and effectively pick up these discursive patterns and reproduce them intuitively. There is no need for explicit manuals, because apprehension of such patterns takes place at the subconscious level of deutero-learning (Bateson 1972). They become part of users’ very cognitive framing and political subjectivities – how they literally come to see the world, and act upon it. As the digital revolution has by now sedimented into our taken for granted infrastructure, and the neoliberal episteme becomes increasingly hegemonic, the notion of political representation, and even of democracy, has to be seriously rethought.

Letícia Cesarino is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Florianópolis, Brazil. She earned her Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley in 2013, and has since then worked and published on South-South cooperation, science and technology, and more recently, on the emerging entanglements between neoliberal globalization, digital media, and democratic politics.

Letícia Cesarino is Associate Professor of Anthropology at the Federal University of Santa Catarina in Florianópolis, Brazil. She earned her Ph.D. at the University of California, Berkeley in 2013, and has since then worked and published on South-South cooperation, science and technology, and more recently, on the emerging entanglements between neoliberal globalization, digital media, and democratic politics.

Works Cited

Bateson, G (1972) Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Chicago University Press.

Mouffe, C (2005) On the Political. Thinking in Action. London: Routledge.

Harding, S (1991) “Representing Fundamentalism: The Problem of the Repugnant Cultural Other.” Social Research 58(2).

Laclau, E (1990) New Reflections on the Revolution of our Time. London: Verso.

Magenta, M et al. (2018) “How WhatsApp is being abused in Brazil’s elections.” BBC News Brazil. October 24.

Mirowski, P (In press) “Hell is Truth Seen Too Late.” Boundary 2 46(1).

A very insightful essay on the strategies that undermined Brazilian voters in the last elections. It’s interesting to note how they were present on both sides of the electoral dispute – right and left wing – as a kind of discursive form that took over the political realm. Parabéns!!!

LikeLike

[…] What history shows is that it’s not the technology which is bad or good. We’ve seen that with the advent of every new media. Instead, each technology has certain affordances that can be relatively authoritarian or relatively democratic (Benkler, Faris, and Roberts 2018, 8). Disinformation relies on the internet’s capillarity to spread, but becomes dangerous in silos. Research in Network Propaganda, linked to just above, shows that the problem in the US election was that the far right was only interacting with the far right, while the rest of the political spectrum was attentive to the far right and also broadly exchanging information. A very distorted version of reality was developed in that isolated silo or bubble, which is one of the ingredients in the radicalization (now discussed mostly around YouTube but also reminiscent of what Letícia Cesarino [2019] has called the Bolsosphere, on WhatsApp). […]

LikeLike